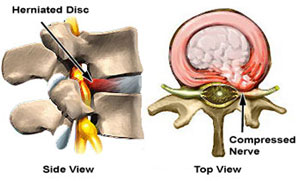

Ernie presented to me a few years ago with severe back and leg pain. He had undergone two spine fusions for LBP about 10 years earlier that had not been helpful. His three lowest vertebra had been fused from L4 to the sacrum. Additionally, he now had severe leg pain from tightly pinched nerves at L3-4, which was the level right above his fusion. It’s common for the next level to break down and require surgery.

He hadn’t worked for many years and was overtly angry at the employer, his family, me and generally the world. He was’t in any state of mind to read a book or engage in any of the tools to calm himself down. I still worked with him for 3 months to at least stop smoking and understand some of the basic chronic pain concepts. His stenosis was so tight that I thought we should still proceed with surgery.

He got worse

I have felt that when a severe surgical problem is solved that the amount of pain relief provided would allow my patients to function enough to move forward regardless of the patient’s state of mind. I surgically removed the constriction around his nerves and fused him at L3-4. The operation went extremely well and his nerves were completely freed. He got worse – a lot worse. Although I am always clear that LBP does not improve with surgery, I was sure that his legs would improve. They didn’t. It was my first hint that chronic pain was more complicated than I thought. I worked with him for almost a year trying to rehab him and finally had to let go.

“Just fix it”

Spine surgery should be performed only for an identifiable anatomic abnormality that is causing matching symptoms. For example, if your 5th lumbar nerve root is being compressed by a bone spur then the pain would travel down the side of your thigh and calf. If the pain is located in a different area, then it would not be considered a structural problem. Surgery performed for a specific lesion generally yields a predictably satisfactory outcome. With this concept in mind, I have historically recommended that if you are suffering from chronic pain and now have an additional structural problem, you should have your operation performed more quickly since your nervous system cannot tolerate the additional insult.

I noticed that the results of my surgeries on clear-cut problems in the presence of long-standing pain weren’t consistent and patients would often be made worse. I had thought that the pain relief afforded by my surgery would compel people to move forward with the rest of their rehab. The severity of the pathology I was correcting was stunning. Ernie’s story is common. One of my fellows succinctly pointed out that whatever pain that is left is now 100% of the pain.

Chronic pain can be a complication of any surgery

I ran across a series of papers that showed that if you underwent a simple uncomplicated procedure, such as a hernia repair, while experiencing chronic pain in another part of your body you could end up in chronic pain at the surgical site up to 40% of the time. (1) Five to ten percent of the time it would become permanent. I was never taught that this was a possibility and it is not usually presented as a potential complication of surgery. If I had an infection rate of 5 – 10%, I would not be in practice for long – and infections are solvable. When will the pain stop?

A different driver

Another paper demonstrated that acute LBP is sensed in a specific pain center in the brain. It is well-known and easily identifiable. However, if you experience LBP for more than a year it switches completely over to the emotional center and the pain center goes quiet. It occurs every time in every patient. You’ll have the same pain but a different driver. (2) Surgery performed for pain in the emotional center is not going to work no matter how compelling the pathology.

Google Talks lecture – note that the host had 3 surgeons recommend surgery and he’s doing fine using the concepts outlined in the DOC process.

Phantom pain

The problem is similar to phantom limb pain. Before a person requires an amputation of his or her leg they’re usually in quite a bit of pain. Over half of amputees still feel their leg AND the pre-op pain they had before the amputation. How can that be? The source of pain is clear and an amputation is definitive. It’s a programming problem. Once these unpleasant circuits are embedded in your brain they are permanent.

One surgeon reported on the results of 11 patients who had their normally functioning arms amputated for pain. The source of the pain wasn’t identifiable. Guess what? None of them had any pain relief and now they had just one arm. It is somewhat of a disturbing article to read.

There is a naïve view that surgery is the definitive answer if everything else has been tried. It’s only the solution if you can see the problem and even then it may not be effective if the “pain switch” in your brain remains on.

Is your surgeon seeing the whole picture?

It turns out that the additional stress of surgery in the presence of a fired up nervous system is a bad idea. The medical literature has shown that anxiety, anger, depression, lack of sleep, length of pain, and taking high dose narcotics all portend a poor prognosis for any surgery. (3) A 2014 research paper out of Baltimore related that only 10% of surgeons were currently assessing these factors before making a surgical decision. The results of surgery were predictably poor without these variables being considered. (4)

Know your surgeon – before surgery

Optimizing surgical outcomes

About four years ago my staff noticed that patients who went through a self-directed structured spine care program, such as the DOC project, had outcomes that were better and the post-operative course was much easier. We call the protocol “prehab” (rehabilitation before surgery). We require that all of our patients who are considering elective surgery spend at least 8 weeks addressing the various aspects of their chronic pain. For some of the more complex situations, we may work them for over a year before his or her situation is optimized for a consistently good outcome. Unexpectedly, over 100 patients in the last several years with major structural problems cancelled their surgeries because his or her pain disappeared.

Out hunting elk

Rick was an active physically fit gentleman who had severe, almost extreme spinal stenosis between his 3rd and 4th lumbar vertebra. The diameter of a normal spinal canal is about 15 mm and his was down to about 4 mm. His leg pain was so severe that he was essentially wheelchair-bound for prior six months. His symptoms and stenosis were so severe that I changed my schedule in order to perform his surgery the next week. BTW, he was not buying any of this “DOC project.” Then he came down with a respiratory infection and we had to delay his surgery for a couple of weeks. I said, “Look Rick, just humor me and at least start the expressive writing.” About five days before his surgery he called me and said that he was feeling a little better. I replied, “That’s great but I am assuming that you still want to do the surgery?” He said that he did. On the Friday before his Monday surgery he cancelled his surgery because he felt fine. When I talked to him a couple of months later just to check in he was back in the hills hunting elk without any pain – with a four mm spinal canal. Several years later he has not undergone any surgery.

Remember that you cannot take your body to the shop for a repair and expect the same percent of success that you would for your car. Cars don’t have a pain system. There is nothing in the mechanical world that remotely resembles pain. Be careful regarding your final decision to undergo surgery? Ask yourself the following questions:

- Am I getting a consistently restful night’s sleep?

- Is my anxiety improving?

- Have I addressed my anger issues? Am I even connected them?

- Are my medications stable and at a reasonable dose?

- Am I optimizing my exercise regime?

- Do you really know the chances of success for your proposed operation?

- Are you willing to accept a significant chance of your pain become worse from the surgery – even without a complication?

Prehab – optimizing surgical outcomes

We now have our patients address these issues and more before every elective surgery. Why not?

- Ballantyne J, et al. “Chronic pain after surgery or injury.” Pain: Clinical Updates. IASP (2011); 19: 1-5.

- Hashmi, JA, et al. “Shape shifting pain: chronification of back pain shifts brain representation from nociceptive to emotional circuits.” Brain (2013); 136: 2751–2768

- Chaichana KL, Mukherjee D, Adogwa O, Cheng JS, McGirt MJ. Correlation of preoperative depression and somatic perception scales with postoperative disability and quality of life after lumbar discectomy. J Neurosurg Spine 2011;14(2):261–267

- Young AK, et al. “Assessment of presurgical psychological screening in patients undergoing spine surgery.” Journal Spinal Disorders Tech (2014); 27: 76-79.

Video: “Get it Right the First Time”