It is an almost universally held belief among surgeons and patients that a specific structural lesion is usually the cause of pain. If that lesion can be identified and repaired, the pain will abate. This seems plausible. A diagnostic test ought to be able to identify the source of intense pain and point to a solution.This simply isn’t the case and in fact, nothing could be further from the truth.

I believed that pain was always structural–I was wrong!!

During my first five years of practice, it was my assumption that if a patient had experienced low back pain for six months, then it was my role to simply find the anatomic source of pain and surgically solve it. I was diligent in this regard. The test I relied on most heavily was the discogram. The discogram is a test where dye is injected into several discs in the lower back; if the patient’s usual pain was produced at a low injection pressure, it was considered a positive response. The only patients I did not fuse were those who did not have a positive response or had more than two levels that were positive. I performed dozens of low back fusions and felt frustrated when I could not find a way to surgically solve my patients’ low back pain.

I have a physiatrist friend, Jim Robinson, who is a strong supporter and contributor to the DOC Project. From 1986 to 1992, we both served on the Washington State Worker’s Compensation clinical advisory board and helped set standards for various orthopedic and neurosurgical procedures. Our discussions were based on this assumption that there always is an identifiable “pain generator.” That means there was always some anatomical problem generating a pain impulse and we need to discover it to save the problem. It was just a matter of figuring out what test is the best one to discern it. We did not think in terms of structural versus non-structural sources of pain. We knew about the role of stress, but did not fully appreciate how large a role it played in altering the body’s chemistry and perception of pain.

BTW, our original concept of a “pain generator” was wrong. The only place in the body where pain is felt is in the brain. Sensory input has to be first interpreted by the nervous system and if a certain threshold is exceeded, your brain sends out a pain signal that indicates danger and your body will respond with an appropriate action to keep you safe. A bone spur has no inherent capacity to generate pain.

Structural problem

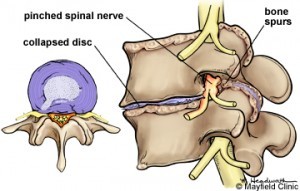

I define a structural lesion as one that is distinctly identifiable on an imaging test, which correlates with the patient’s symptoms. An example would be a ruptured disc pinching a nerve that causes pain down the leg. A ruptured disc between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae will cause pain down the side of the leg. This is the pathway of the fifth lumbar nerve root. A ruptured disc between the fifth lumbar and first sacral vertebra will cause pain down the back of the leg, which is the pattern for the first sacral nerve. If in either of these two examples the pain was going down the front of the leg, it would not be considered the cause of the pain because that is the path of the fourth lumbar nerve root and it does not match.

Other examples are:

- Bone spurs on one or both sides of the spinal canal with matching leg pain and/or nerve damage

- Central spinal canal constricted by bone or ligaments with one or both legs feeling weak, tired, or painful

- Isthmic spondylolithesis (slippage) with corresponding leg pain.

- More that 3 mm of back and forth motion on X-ray if only back pain; This would be considered unstable.

- Degenerative spondylolithesis (slippage) AND canal constriction with corresponding leg pain or fatigue

- >3mm of instability if just back pain; considered unstable.

- Acute compression fracture with fluid on the MRI (indicates bleeding).

- Acute unstable fracture/dislocation

- Tumor

- Infection

- Flatback—whole body tilted forward because the normal curvature of the lower back has been straightened – many causes.

- Scoliosis that progresses over time-just the presence a curve does not count.

Pain problem

Many of you experience pain whose source is not identifiable on any test modern medicine has to offer. When there is no identifiable structural source of your pain, we cannot surgically treat it. But we can still help you and the good news is that you don’t have to undergo the risks of spine surgery.

The only scenario that surgery should be even considered is in presence of an identifiable problem with matching symptoms. Other factors such as the severity of the pain compared to the involved risks must be taken into account. If you can’t see it you can’t fix it.